In the heart of modern Athens, its streets pulsating with traffic, stands an enormous open space bordered by trees and shrubs – the Olympieion – a tranquil archaeological park where earth and sky seem to meet, linked by massive marble columns stretching upward, marking the temple of Olympian Zeus. Once inside the entrance of this age-old sanctuary, visitors are treated to a taste of nature, an extraordinary ancient ruin on a super-human scale and one of the area’s most inspiring views of the temple-topped Acropolis. Our contributing archaeologist John Leonard outlines its history through the ages and why it should be on every visitors itinerary to Athens.

The age-old sanctuary of Olympieion in central Athens. Photograph: DP/Olgacov

More than six centuries in the making

Like the Acropolis, the temple of Olympian Zeus has been a distinctive Athenian landmark since time immemorial. Begun about 520 BC by the tyrant Peisistratus and his sons, it was left unfinished at the end of their rule until the 2nd century BC, when further construction was briefly undertaken (174 – 164 BC) by one of Athens’ Hellenistic benefactors, the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Abandoned once again following Antiochus’ death, it was ultimately finished by the Roman emperor Hadrian and dedicated in AD 132. Hadrian, an ardent Hellenophile much respected by the people of the Greek East, gave Athens not only the completed Olympieion, but also other temples in the area; a new public forum on the north side of the Acropolis that contained a library and lecture halls; and an urban water system fed by an aqueduct from Mount Penteli that continued to supply the city until the 1930s.

Take an audio tour of the Temple of Olympian Zeus

The Olympieion with its distinctive temple and the arch of Hadrian in foreground as seen from the Acropolis. Photograph: Why Athens

A pleasant refuge

The original centre of the Greek city of Athens, surrounding the Acropolis, was supplemented during Hadrian’s time (ruled AD 117 – 138) with a new affluent neighbourhood that grew up around the Olympieion, on the north bank of the Ilissos river – a district extending today from Ardittou street (beside which water still occasionally flows) to the Zappeion Hall, the National Gardens, the Greek Parliament and Vasilissis Sophias avenue. This relatively lush area of the Ilissos river, which descended from Mt. Hymettus and was supplemented by the copious Kallirroe Spring, offered ancient Athenians a cool, shady place to stroll. As Plato reports, Socrates once invited Phaedrus there “to sit down quietly wherever we please” (Phaedrus 229). The youth replies, “I am fortunate, it seems, in being barefoot; you are so always. It is easiest then for us to go along the brook with our feet in the water, and it is not unpleasant, especially at this time of the year and the day.”

Hadrianopolis

Contemporary visitors will find a variety of antiquities worth seeing in the Olympieion area besides the temple of Olympian Zeus: portions of the city’s Themistoclean Wall and Ninth Gate, completed in 479 BC using architectural “spolia” that includes unfinished column drums from the Peisistratid era; an elaborate Roman bath complex (under a roof beside Vasilisis Amalias avenue); the foundations of well-to-do Roman houses; and a marble-floored Early Christian basilica (5th/6th c. AD) that also incorporates architectural remnants from the Zeus temple.

The monumental, Corinthian-style Arch of Hadrian is an unmissable landmark in Athens. Photograph: Why Athens

The monumental, Corinthian-style Arch of Hadrian marked a ceremonial transition from original Athens to the new Roman suburb of Hadrianopolis – its two facades bearing Greek inscriptions just above the main arch that announce, on the Acropolis side, “This is Athens, the ancient city of Theseus,” and, on the opposite side, “This is the city of Hadrian, and not of Theseus.”

In its prime under Hadrian, the temple of Olympian Zeus was an octostyle, dipteral temple, meaning it had eight columns across its narrow ends, with twenty down its long sides, while its total of 104 columns that enshrouded the central cella were generally arranged in two surrounding colonnades. Inside the cella, two two-tiered rows of columns lined the room’s long sides, flanking a large gold-and-ivory cult statue of Zeus. With the external columns each 17 m tall and 2 m in diameter, the temple must have appeared to ancient visitors like a dense, towering forest of marble trees.

The columns of the temple of Olympian Zeus appear like a towering forest of marble trees. Photograph: Why Athens

The Corinthian Order capitals of the Olympian Zeus

The Olympieion’s Corinthian capitals were mostly the work of the Roman architect Decimus Cossutius, employed by Antiochus IV Epiphanes during the temple’s Hellenistic building phase.

The Corinthian capital was originally a Peloponnesian invention, combining a lower zone of naturalistic acanthus leaves with similarly vegetal but more stylized volutes above. On each face of the capital, a central sturdy stem between the springing volutes rises to a flower that partly overlaps the abacus above.

The Corinthian Capitals were inspired by a thriving acanthus plant in the Peloponnese. Photograph: Why Athens

The capital, according to Roman author and architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, was inspired by a thriving acanthus plant, seen one day in Corinth by the sculptor Callimachus, which was growing up around the outside of a tile-covered basket and springing outward at the top.

Imperial cult and Panhellenic ambitions

The Greek traveler, Pausanias (mid-2nd c. AD), who visited the Olympieion not long after its completion, provides a firsthand description of the sanctuary, reporting that “before you go into the temple…, there are two portraits of Hadrian in Thasos stone and two in Egyptian stone. In front of the columns are the bronze figures which the Athenians call the Colonies…” In addition, “the whole enclosure is half a mile around, all full of statues. Every city dedicated a portrait of the emperor Hadrian, but Athens outdid them by erecting the notable colossus behind the temple” [i].

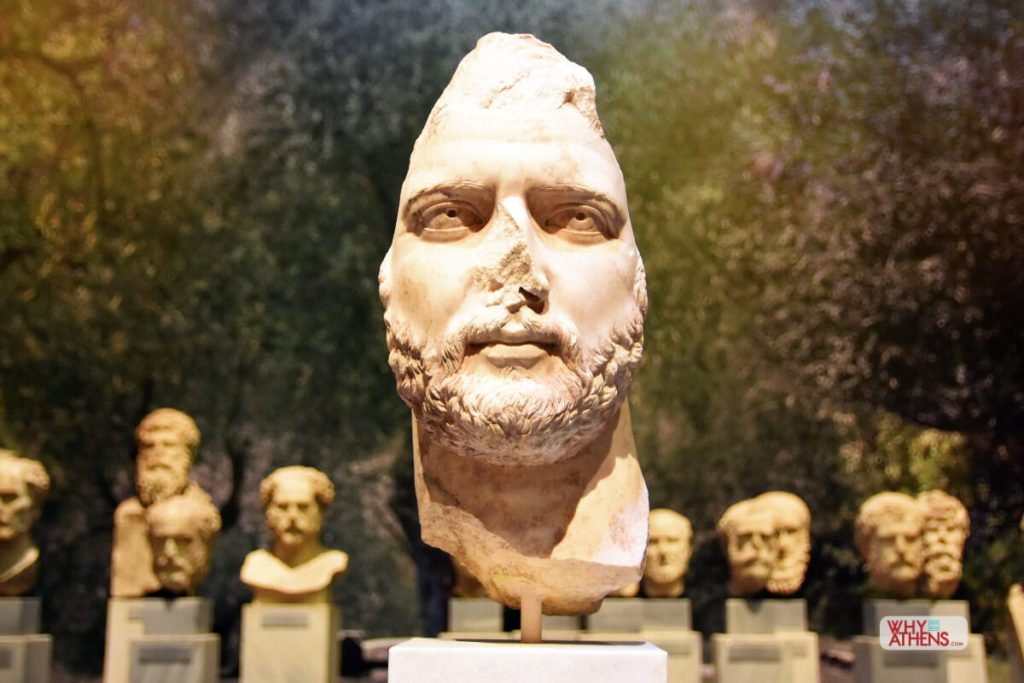

A portrait sculpture of Hadrian made from Thasian marble circa 130-140AD on display in the National Archaeological Museum. Photograph: Why Athens

Indeed, despite the Olympieion being ostensibly dedicated to Zeus, its true focus of worship was Hadrian, who promoted the Athenian temple and its precinct as a major base for the imperial cult in the Greek East – a region of his empire that he aimed to unify through the power of his influence, pro-Greek reputation and generous public benefactions. Also, in establishing Athens as the headquarters of the Panhellenion, a league of eastern Greek cities founded in AD 131, he erected between the Olympieion and the Ilissos river a second large temple dedicated to Zeus Panhellenios and Hera. The emperor’s presence was felt throughout the city, not only from his many public statues but also nearly a hundred stone altars bearing honorific inscriptions.

Fallen columns

Unfortunately, the Olympieion did not survive long in its brilliant final form. A century after Pausanias, Athens was attacked by northern invaders. To defend against these assaults, a new city wall was hurriedly erected during the reign of the emperor Valerian (AD 253-260) – for which project the city’s builders quarried stone from existing structures in the adjacent Zeus sanctuary. This was not the first time the temple had been exploited for building material, as when Athens was previously overrun by the Roman general Sulla’s army in 86 BC, some of the then-still-unfinished building’s internal columns were carried away to Rome and used in decorating the Capitoline temple of Jupiter[ii].

A violent earthquake on October 26, 1852 toppled one of the massive columns where it still remains today. Photograph: Why Athens

By the 15th century, only about twenty-one of the temple’s massive columns remained standing and its original purpose was becoming lost in time. Visitors to the site, such as Cyriac of Ancona, were told this was the ruin of the “Palace of Hadrian.” Its deterioration continued, with one of its marble columns “felled” and burned for lime by a Turkish governor of Athens in the 18th century. A violent earthquake (or some say a wind storm) on October 26, 1852 toppled another – the huge fallen shaft still to be seen today, lying prostrate and disjointed at the temple’s west end.

Stylite monks

The fifteen columns of the Olympieion that remain standing have long been an iconic feature of the Athenian landscape, described in many a traveler’s recollective account and appearing in numerous paintings, sketches and photographs. Sharp-eyed observers of these images will note an odd structure built on top of the ancient columns – a mysterious, never-forgotten detail.

Herein lies one of the strangest, most intriguing stories behind the Olympian Zeus temple’s colourful past, for it seems Hadrian’s columns became the base for a Byzantine watch tower, three stories high, which provided late antique Athens some protection on its eastern side.

Johann Michael Wittmer’s 1833 painting ‘View of Athens from the River Ilissos’ features not only the fallen pillar in it’s erect state, but also the odd structure built on top of the ancient columns. Painting: Benaki Museum collection

Later, abandoned by the city’s garrison, this structure was taken over by a series of Stylite monks, first mentioned by the early traveler and painter Edward Dodwell in 1805-1806. Their extreme ascetic practices led these monks to seek refuge from the material world, and closer to God, by making their home on top of tall columns or pillars (styloi).

Another visitor to the Olympieion, Alexander Wilbourne Weddell, a former American consul, writes in the December 1922 National Geographic magazine, “We took a seat on the base of one of the columns and looked up to its top… During my stay at Athens I was assured by an old Athenian that he remembered as a child visiting the precincts of the temple and carrying gifts of bread and fruit to the stylite who then dwelt on the column and who would let down a basket to receive the offerings of visitors.” Today, the monks are gone and the ruin on the Olympieion’s columns no longer visible (removed by archaeologists in 1870), but Zeus and Hadrian’s sanctuary-turned-archaeological site remains a pleasant refuge, steeped in Athenian history.

Take an audio tour on your visit to the Temple of Olympian Zeus here

Why Athens Tip: The Panathenaic Stadium is within walking distance.

Find more must see attractions in Athens here.