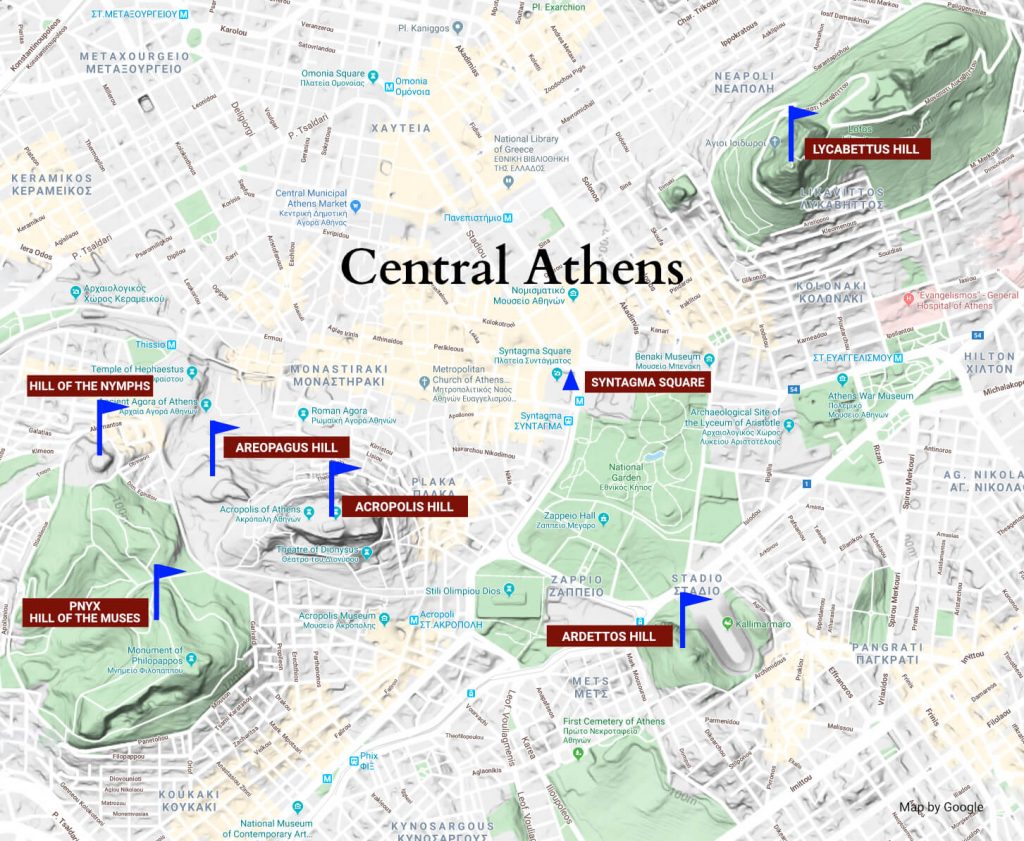

For walkers, hardcore hikers or simple nature lovers, the hills of Athens offer a delightful opportunity to escape the city and appreciate Greece’s varied, inspiring, age-old landscape.

In ancient Athens, these monumental natural elevations, sharply distinct from their surrounding terrain, were usually not inhabited but reserved for sacred, ceremonial or governmental purposes. More than a dozen major prominences were familiar features for ancient Athenians, beginning with the steep, rocky Acropolis at the city’s centre.

The Acropolis

Every Athenian hill-tour should begin with the Acropolis – the jewel in the crown of the powerful Classical statesman Pericles. He revived the central hilltop sanctuary of Athena and reinvigorated his fellow citizens, some three decades after the Persians’ stinging invasion of Athens in 480 BC, by reorganising this most important religious site and rebuilding its monumental structures – most notably the Parthenon – in gleaming white Pentelic marble.

The Acropolis stands tall in the centre of Athens. Photograph: Why Athens

The combination of Doric and Ionic architectural styles in the Parthenon and Propylaia (the hill’s monumental gateway) was a subtle socio-political message concerning Athenian unification of the mainland and Aegean/Western Anatolian Greek worlds.

The temple of Athena Nike also contributed to the Acropolis’ role under Pericles as a centre of patriotic propaganda, displaying sculpted reliefs that highlighted Greek – particularly Athenian – military victories.

The temple of Athena Nike with its sculpted reliefs sits at the entrance of the Acropolis. Photograph: Why Athens

The Erechtheion, meanwhile, dedicated mainly to Athens’ legendary king Erechtheus and Athena, was a purely religious monument, the most important on the hill, which celebrated Athens’ mythical past and sacred traditions. Its innovative, composite, design – with various internal worship-spaces and projecting north and south (Caryatid) porches – reflected the unprecedented move by Pericles to gather the major cults of the Acropolis into one spot, under one roof. A small, wall-enclosed sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia once existed between the Parthenon and Athena Nike temple – today, most distinguishable to visitors by a set of steps carved in the bedrock, visible just beyond the Propylaia, as one ascends onto the Acropolis summit. (Map point – Acropolis of Athens)

Areopagus Hill

Conspicuous on the Acropolis’ west slope is a bare outcropping that served as the stone pedestal for ancient Athens’ highest judicial body – the Areopagus court. Already established by Periclean times, this council, composed of highly respected former archons (equivalent perhaps to present-day prime ministers) and appointed for life, oversaw trials for deliberate, malicious murder, injury, poisoning and arson, according to Aristotle.

Areopagus Hill is a favourite for both locals and tourists at any time of the day. Photograph: Why Athens

It also conducted high-level investigations and represented the ultimate guardian of the Athenians’ welfare and cherished democracy. Mounting the stone steps to the hill’s summit, you can spy carved in the rock worn traces of former structures, including a temple, and stand where Saint Paul once did as he addressed the Areopagus court and proclaimed the virtues of the Christians’ God. Below the Areopagus was the cave and sanctuary (now inaccessible) of the mythical Erinyes (Fates/Furies), who exacted vengeance against murderers, and to whom, the traveller Pausanias (2nd cent. AD) reports, those acquitted in Areopagus court offered sacrifices. (Map point – Areopagus Hill)

Hill of the Nymphs

The domed roof of the National Observatory of Athens conceals its telescope atop the Hill of the Nymphs. Photograph: Why Athens

Beyond the Areopagus rises the so-called Hill of the Nymphs, a prominent rocky knoll on which today stands the National Observatory of Athens (1842), with its recently restored telescope. An inscription of the 5th century BC inscribed in the bedrock west of the Observatory refers to the Demos (municipality/people of Athens) and the Nymphs. Clearly, this distinctive hill was once sacred to these nature deities and likely held an extra-urban shrine or altar dedicated to them. (Map point – Hill of the Nymphs)

Pnyx, Hill of the Muses

Philopappos Hill, identifiable by its monument on the left and Pnyx Hill on the right. The Odeon of Herodes Atticus is in the foreground. Photograph: Why Athens

Separated from the Hill of the Nymphs by a low saddle, the adjacent Hill of the Muses extends southward – its extremities also known respectively as the Pnyx and Philopappos Hills. It was on the theatre-like open slope of the Pnyx that the Ekklesia, the People’s Assembly, met ten times a year to vote on important governmental matters presented to it by the Vouli, the Council of 500, whose own meeting hall stood below in the Agora.

The view from Pnyx Hill where the People’s Assembly congregated at the start of democracy. Photograph: Why Athens

Here, the Athenians were treated to moving, persuasive, often fiery speeches delivered by Themistocles, Pericles, Cleon, Alcibiades, Demosthenes and other key figures advocating new laws, actions or honorary resolutions, defending accused fellow-citizens or railing against the city’s opponents, who over time included the Persians, the Spartans and Philip II of Macedonia. Today, an impressive, stepped rock-cut speakers’ podium (bema) can still be seen – established in the 4th century BC when the auditorium’s orientation was reversed – as well as portions of a massive retaining wall that supported the area’s northern perimeter. (Map point – Hill of the Muses Philopappos)

Ardettos Hill, Panathenaic Stadium

The monumental Panathenaic Stadium (Kallimarmaro) lies between the twin peaks of pine-clad Ardettos Hill. The stadium was originally constructed by Lykourgos in the 330/329 BC for the games of the Panathenaic Festival but was refinished in white Pentelic marble in the 2nd century AD by Herodes Atticus.

The pine-clad Ardettos Hill surrounds the Panathenaic Stadium and overlooks the temple of Olympian Zeus. Photograph: Why Athens

Restored in the late 19th century, it became the home of the first modern Olympic Games in 1896. On the higher western summit of Ardettos Hill stood a Roman temple of Tyche (Fortuna), whose foundations of large squared blocks are still visible, while on the eastern rise are traces of a 40 m – long pedestal that may have held the ship-float used in the Panathenaic procession of AD 140. The great benefactor Herodes Atticus himself may have been buried in an elaborately decorated sarcophagus discovered nearby and now displayed at the upper eastern edge of the stadium. (Map point – Ardettos Hill)

Lycabettus Hill

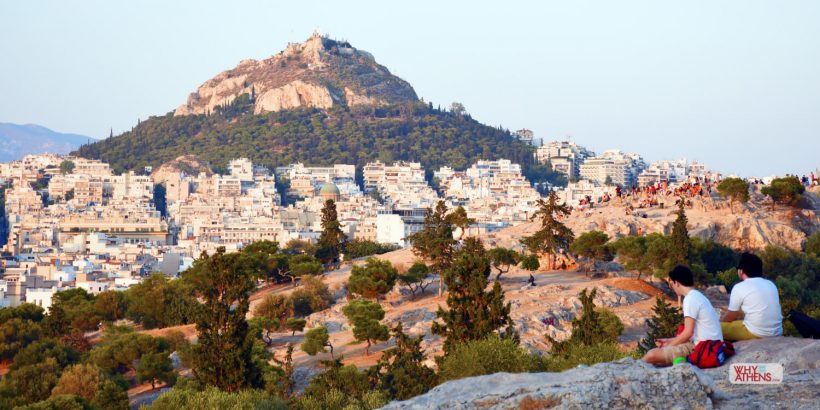

Lycabettus Hill is one of the most distinctive landmarks in Athens. Photograph: Why Athens

The ancient use of Lycabettus Hill remains one of the great conundrums of Athenian archaeology. Although often described as bare of temples or other sacred ancient remnants, Lycabettus (“Wolf Mountain”) – like all of Athens’ other prominent hills and mountains – was likely the focus of worship for some today-unknown god or group of deities.

The highest point in central Athens, Lycabettus Hill provides a panoramic view of Athens’ best landmarks. Photograph: Why Athens

A distinctive landmark visible from virtually everywhere in the valley of Athens, Lycabettus is now crowned by the small chapel of Aghios Georgios (1870), while on its southern slopes are a mixture of noteworthy ancient and contemporary sights, including the ruins of the monumental Roman reservoir (“dexameni”) fed by the city’s Hadrianic aqueduct (Dexameni Square); the little-heeded eponymous Roman column that marks Kolonaki (“small column”) Square; the neo-classical Gennadius Library (1926), a centre of post-antique Greek studies; and the Moni Petraki (18th century), whose upland sheep pastures once tended by reclusive monks provided the land for the adjacent American (1881) and British (1886) archaeological schools. (Map point – Lycabettus Hill)

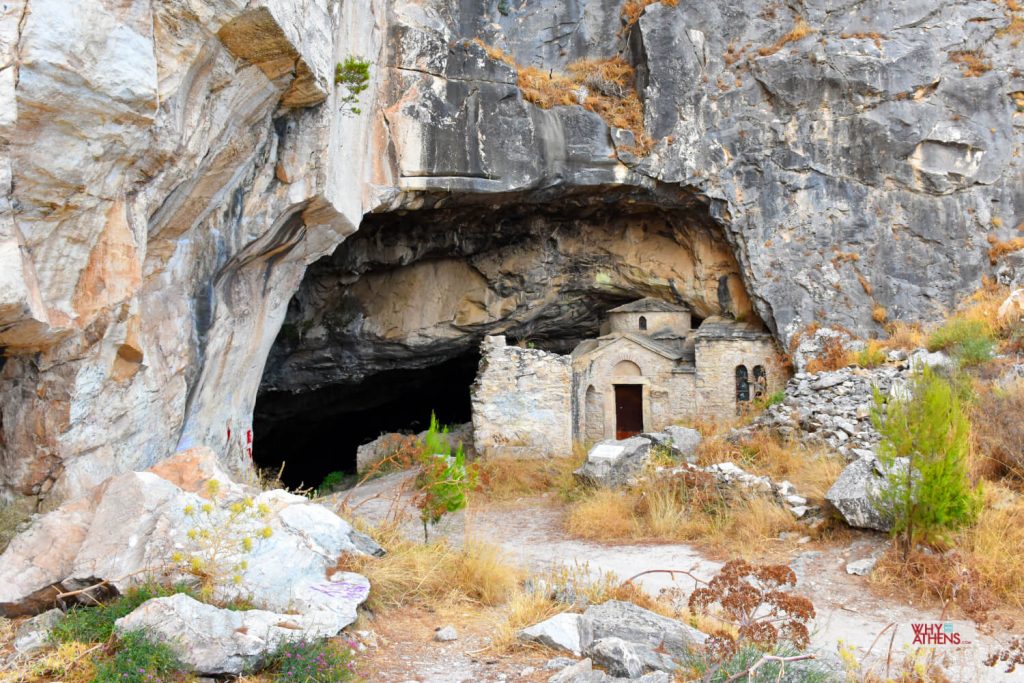

Mts. Penteli, Hymettus, Parnitha

The mountains surrounding the Athens valley are all worth exploring. Mt. Penteli (Pentelikon) was the source of the white marble used for the Periclean refurbishment of the Acropolis, as well as by Herodes Atticus for the Panathenaic Stadium. Among the ancient quarries, still clearly visible from the city, the largest, Spilia, includes a deep, high-ceilinged cave with a double Byzantine chapel at its entrance (Saints Nikolaos and Spyridon) of the 11th or 12th century. Behind the main mountain, a modern quarry in the town of Dionysos supplies marble of closely similar quality to that of the ancient quarries for the present-day Acropolis restorations. A small nearby sanctuary of Dionysus marks the rural area from which the travelling performer Thespis is believed to have first brought dramatic performances with music and dance to Athens. Pausanias reports the existence of a statue of Athena on Penteli’s summit.

The double Byzantine chapel at the entrance to the Davelis Cave at the ancient Spilia quarry on Mt Penteli. Photograph: Why Athens

Mts. Hymettus and Parnitha (Parnes) were also sacred mountains, on which were erected altars and statues of Zeus Ombrios – the cloud gatherer and bringer of rain. The statue on Parnitha was bronze (Pausanias 1.32.2). Pan also inhabited the forested slopes of these ranges, with caves dedicated his worship. Hymettus was particularly famous in Roman times for its bees, wild thyme and delicious honey. Inscriptions carved in the bedrock in the foothills near Kaisariani declare “OROS” or “boundary” – engraved by local beekeepers who thus marked their personal territories. At the base of Parnitha lay ancient Acharnai (Acharnes), the most populated deme of Classical Attica. The Roman poet Statius (1st cent. AD) wrote that Parnitha was rich in vines, Lycabettus richer in juicy olives, the air of Hymettus fragrant and the slopes of Aigaleo thick with forests (Thebaid 12.620 ff.). Today, Hymettus and Parnitha continue to offer pleasant escapes with trails for hikers and other nature or history lovers. (Map point – Mount Penteli)

Want to discover more of Athens? Learn all about the churches of Athens and the remains of Byzantium here.